This blog is now closed. But if you are after information, news and opinions on the human rights of tea workers, the tea industry’s challenges in upholding them, and thoughts on how they can be overcome, go to the website of The International Roundtable for Sustainable Tea – THIRST. See you there!

How is coronavirus affecting your precious cuppa?

The minute there was a whiff of shortage in the air – when the then still unfamiliar word “lockdown” was first being whispered – it triggered in the British a throwback, kneejerk reaction to post-WWII rationing times… The population made a beeline for the supermarkets to stock up against the coming Apocalypse.

Social media images of empty shelves receding into the distance instantly revealed what Brits value most; toilet paper, flour, tinned tomatoes, pasta and hand sanitizer. And they also bought 55% more tea than the same time last year. Tea bags were one of the essential items included in government food parcels for “extremely medically vulnerable people.”

But at the end of March, Indian tea estates were forced to shut down in the country’s own coronavirus lockdown, tea factories and auction houses fell silent, transport rumbled to a stop, buyers stopped coming to estates, India’s other big customers – like Iran and China – cancelled their orders, millions of kilos of tea piled up in ports…and the price of Indian tea plummeted by 40%.

Tea pluckers are paid only for the days they come to work, and based on how much tea they pluck. No plucking usually means no pay. The Indian Government said that (despite tea estate owners’ loss of income) workers must be paid… permanent workers, that is. The army of temporary workers, a growing proportion of India’s tea workforce, had no such protection. In practice, many of the permanent workers missed out on pay too despite the Government ruling.

The more responsible tea estate owners sanitised banknotes (no on-line banking in the remote hills were tea is generally grown) and delivered them door-to-door to prevent possible infection. Others donated free rations to temporary workers who would otherwise have gone hungry.

Meanwhile, workers and managers alike were forced to sit back and watch the fresh young leaves of their most valuable ‘first flush,’ crop – the “Champagne of tea” – grow, darken and toughen… and finally be lost altogether.

A heart-breaking choice now had to be made. To save their businesses – and thousands of jobs – some tea plantation owners begged the government to let them resume work before they lost the second flush too – the one that grows in after the first flush is harvested. But to save tea workers from the risk of infection with this ruthless virus, other owners – alongside trade unions and NGOs – expressed alarm at the idea of resuming work on tea estates.

The compromise was to allow them to reopen with only 25% to 50% of the workforce working at any one time, strict social distancing, and with handwashing facilities available and personal protective gear provided.

The historic and widespread challenges of low pay, poor sanitation, overcrowded housing and inadequate healthcare could have meant (and could still mean) the virus spreading like wildfire through tea estates. But thankfully, to date, the infection rate in tea growing areas has been minimal. The insular nature of tea estates, a history of tight security managing who enters and leaves them, and where and when the live-in workforce goes has perhaps made it more feasible to manage the spread of the virus in these lush corners of India.

And yet, the freezing of multiple links of the supply chain means that some companies may never recover from this latest brutal hit. We’ve already seen in places like West Bengal, that when tea estates close down, people starve. After generations of dependence, tea workers often have no alternative skills, land or income sources to fall back on… and repurposing land to grow food where tea has grown for nearly two centuries requires resources that they simply do not have.

The Indian tea industry was already reeling from multiple economic hits pre-COVID19. As it emerges from this latest crisis, going back to the status quo may not be an option. But perhaps from the jaws of disaster, we can draw some glimmers of hope. An opportunity to do things differently. To “build back better” – as the United Nations, and many others are suggesting.

Because of COVID19, the Assam government has offered to step in and take over the hospitals, clinics and creches that, until now, the already overstretched tea companies were expected to provide. If this actually happens (it hasn’t yet, though free medicines have been provided) keeping it in place could mean that tea companies will in future have more cash available to spend on improving workers’ pay and housing (and workers should get better quality healthcare).

Because of COVID19, Fairtrade International has amended its guidelines so that “producer organizations can spend Fairtrade Premium funds more flexibly to minimize the spread of disease…” Keeping that flexibility in place could mean that tea plantation workers get more of their basic needs met. But for this to have significant impact, Fairtrade certified tea will need to be sold in much greater quantities…. only 10 of Assam’s 800 tea estates are Fairtrade certified, for example.

Because of COVID19 panic buying, Brits demonstrated that tea is one of their most valued shopping list items. Being willing to pay a price that reflects this value – and reflects what it would actually cost if workers got decent pay and benefits, would show our supermarkets that we really do care about this. And our supermarkets sharing that price fairly with producers, could be the shot in the arm that the Indian tea industry needs to boost its immunity to the multiple challenges it is facing. The industry only exists, after all, because of Britain’s love of the drink.

The royal virus – the great equaliser?

“A tiny piece of genetic material wearing a lipid coat and a protein crown” is how Zania Stamataki describes “this little virus holding the world to ransom.” I have an image of a microscopic evil cartoon prince, wielding a tiny, blazing – and disproportionately lethal – sword…

When Prince Charles and UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson were struck low by Prince Covid XIX, journalists said this showed that the virus was a great equaliser… although as human royals and rulers are generally made of the same biological material as ordinary mortals, I’d have thought immunity by virtue of status was unlikely.

The current US President appears to believe otherwise, saying that while his medical advisors recommend everyone wear face masks to slow the spread of the virus, he wouldn’t be doing so, because he’d be meeting with “presidents, prime ministers, dictators, kings, queens – I don’t know, somehow I don’t see it for myself.”

But then pop royalty, Madonna, reiterated the point in her Ophelia bath-tub moment; “That’s the thing about Covid-19,” she said. “It doesn’t care about how rich you are, how famous you are, how funny you are, how smart you are, where you live, how old you are, what amazing stories you can tell. It’s the great equaliser. And what’s terrible about it is what’s great about it. What’s terrible about it is that it’s made us all equal in many ways, and what’s wonderful about it is that it’s made us all equal in many ways.”

True. But then the same is true for every other virus and disease.

Yes, everyone can get it. But not everyone can survive it. We now know that the elderly and frail – those with ‘underlying health issues’ are more likely to develop serious complications, and to die from them, so there’s an age and health inequality in the equation…

Then racial inequality reared its ugly head; another American musician with pretensions to virology expertise announced (echoing similar rumours in African countries) that “minorities can’t catch it”. But alas, they can. They do. They have. And in the USA, they are dying in higher proportions than their majority counterparts.

Why?

Because, Prince Covid XIX’s fiery sword shines a searing light on another – more ubiquitous – kind of inequality. The economic kind; one of the main issues underlying those ‘underlying health issues’ like diabetes and heart conditions – is poverty.

The fiery sword cuts its swathe through not just lives, but also livelihoods. And as the organs that produce the goods we buy, the arteries and veins along which our ships, trains and planes carry them, the wealth that nourishes the body of global trade all grind to a halt under the attack from this presumptuous little invader – the desperate vulnerability of the poorest is laid bare.

Like the internal migrant workers of India, invisibly toiling in people’s homes, construction sites, textile factories, plantations… missed out of the government’s reckoning when they imposed a lock-down at four hours’ notice. An estimated 6 million of them suddenly lost their precarious incomes, and with transport on lockdown too, many were compelled to walk – sometimes hundreds of miles – back to their villages. Some died of exhaustion and starvation on the way. Indians had seen nothing like it since the mass movement of people prompted by Partition 1947.

Of course, the focus of this blog is normally on tea plantation workers, and here again vulnerability is laid bare. The World Health Organisation advises that to defend yourself from Prince Covid all you need to do is wash your hands with soap and stay 2 meters apart. Yet to do that you need plenty of accessible clean water – and soap! And houses big enough for you and your family to practice social distancing during lockdown… The virus has not yet arrived, yet its impact is already being felt as tea estates are under lockdown, tea buyers have vanished, auction houses have shut down and there is no money to pay these daily wage workers.

If (let us pray not when) the virus passes through the gates of the first tea estate, it could spread like wildfire. How will their clinics and hospitals, straining already to cope with normal levels of illness, cope? The Indian government may step in to help temporarily. But perhaps if the sum you pay for the tea you have likely stockpiled in your pantry, was shared more equally with plantation owners – they could use it to protect their workers.

And finally, the Prince Covid’s lightening sword is highlighting who society really needs in times of crisis. We can manage without highly paid footballers, and Princes of the realm. We even seem to be managing temporarily without a Prime Minister. But we absolutely can’t manage without our underpaid nurses, refuse collectors, bus drivers, supermarket workers… those we now know as our “key workers”. We took them so much for granted before. And now we regularly applaud them from our doorsteps and windows. Perhaps we should also think about paying them a living wage?

Former World Bank lead economist, Professor Branko Milanovic, says “Economic history shows epidemics are great equalisers. The most cited example… is still the Black Death… by reducing population, it made labour more scarce, increased wages, reduced inequality and led to institutional changes which… had long-term implications for European economic growth.”

For all the tragedy, sorrow, fear, loneliness, pain, poverty and bereavement that Prince Covid XIX has wreaked upon the world, perhaps when his reign is over, he will leave us readjusting our values and striving for a more equal global society. A society in which, when the next pandemic hits – and it will – we will have organised things so that everyone will have economic immunity and no-one’s life will be compromised by poverty.

A Happy New Decade for Tea Workers!

Exactly half way through this last decade, the women tea workers of Munnar in South India rose up and said ‘Enough’. They demonstrated against the tea company for keeping them in poverty, against the trade unions for not representing them fairly, and against the politicians not doing anything to protect them. Many tea-pun headlines later, the world’s media concluded that this plucky group of women had “won”[i] (their 20% bonus) and moved on to fresher stories.

Exactly half way through this last decade, the women tea workers of Munnar in South India rose up and said ‘Enough’. They demonstrated against the tea company for keeping them in poverty, against the trade unions for not representing them fairly, and against the politicians not doing anything to protect them. Many tea-pun headlines later, the world’s media concluded that this plucky group of women had “won”[i] (their 20% bonus) and moved on to fresher stories.

Meanwhile the women remain in their tiny dilapidated houses, the bonus that they fought for reverted to the earlier lower rate, their daily wage rate increased slightly but only on condition that they plucked yet more tea.

As the new decade begins, the age old problems persist. But I strongly believe that the tea industry has the power to change. The catalogue of problems that follows does not have to reflect the decade to come. But it can inform a determination to turn the industry around and adopt pricing and labour practices that invite admiration rather than criticism.

“The more things change…”

And a lot has changed in India in the 200 years since tea was first planted there. Independence. Land redistribution by the Communist governments of tea-growing states, Kerala and West Bengal. A burgeoning middle class. Soaring GDP. Yet somehow tea estate workers remain exempt from progress – kept frozen in 19th century feudalism and penury.

The pitifully low wages paid to them, the shoddiness of their housing, their lack of access to clean water and to decent healthcare has come up before.

In 1866, 1900, 1955, 2004, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2019 to be precise. There are many, many other instances of these issues being raised, but these are the dates of the reports by NGOs, trade unions, the media and academic institutions that I reviewed last year for THIRST – The International Roundtable for Sustainable Tea – to trace just how long the problems have persisted, with a focus on Assam.

The answer seems to be… from the very beginning.

That’s why Columbia Law School entitled their 2014 report, “The More Things Change…” referencing the epigram “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” or “the more things change, the more they are the same.”

“below the poverty line” & “life-threatening malnutrition…”

Low wages reported in 1900, 2008, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2019

In 1900, the Chief Commissioner of Assam, Henry Cotton, wrote of tea workers there: “Not only were their lives worse than that of American Slaves but their living and working conditions were also deplorable… Their wages remained frozen at the rate of Rs 5 per month for men and Rs 4 for women established by a statute in 1865.[ii]”

One hundred and eight years later SOMO said; “… malnutrition on tea estates is still a big problem which leads to all kinds of medical problems including in some cases infant death and starvation.” Two years after that, War on Want reported “The children of tea workers in Assam suffer due to their parents’ low wages and miserable living conditions, as evidenced by the high prevalence of malnutrition.” And in 2016 The Global Network on the Right To Food and Nutrition (GNRTFN) found evidence of “several malnutrition-related deaths” due to management failing to provide mandatory food rations (which are considered part of the pay package).

Columbia Law School, in 2014, raises the issue of deductions from these low wages – an issue raised by Cotton one hundred and thirteen years earlier; “In some instances only a few annas (or pence) found their way into the hands of a coolie as wages in the course of a whole year, the managers having deemed that they were justified in making deductions right and left so long as they kept their labourers in good condition like their horses and their cattle.”

Traidcraft reminds us in 2019 that; “women working on tea estates are paid significantly less than those working in other areas of agriculture, for what is difficult and skilled work.” And Oxfam reports that official recognition of tea workers’ poverty is evidenced by the fact that, shockingly, “half of households interviewed receive government ‘Below Poverty Line’ ration cards.”

“cramped quarters with cracked walls and broken roofs…”

Inadequate housing reported in 1955, 2010, 2014, 2016 and 2019

Iris MacFarlane – the wife of a tea plantation manager in the 1950’s – described workers’ accommodation as “…rows of thatched hovels sharing a communal tap.” By the time War on Want reports in 2010, the situation is not much better; “Whilst housing is provided, it is of poor quality and in need of maintenance.” The theme echoes again and again through the decades; Columbia Law School in 2014; workers “live crowded together in cramped quarters with cracked walls and broken roofs.” Traidcraft and Oxfam in 2019; “Houses are often extremely old and leaky and the management appears unwilling or unable to make the necessary repairs,” and “workers reported that leaking roofs have meant their families had to use umbrellas inside the house during the rainy season.”

“a network of cesspools…”

Lack of access to clean water and sanitation reported in 1955, 2010, 2014, 2016 and 2019

War on Want reported in 2010 that on Indian tea estates “access to safe drinking water is an acute problem,” citing a study[iii] that found “the same regrettable conditions were the norm rather than the exception.” Again, not much had changed since Iris MacFarlane saw several households sharing a single tap, and thought “No wonder the servants suffered from boils and colds.”

Further reports drip persistently through the ages: Traidcraft in 2019; “The lack of proper toilets throughout estates is a major threat to good hygiene standards”. Columbia Law School in 2014; “The failure to maintain latrines has turned some living areas into a network of cesspools…” Oxfam in 2019; “despite doctors’ warnings they have no choice but to drink the contaminated water, so diseases such as jaundice, cholera and typhoid are common.”

“they die here very easily…”

Poor healthcare reported in 1866, 1955, 2008, 2010, 2014 and 2019

A 1866 letter from an Assam tea plantation manager with no medical training describes his approach to medical care for 450 people; “ Every morning I have to administer oil of caster to a lot of them. I have splendid receipt for spleen and have cured a lot of chaps, and dysentery too, two of them are dead but they die here very easily so they don’t think much of that.”[iv]

By 1955 there were hospitals and doctors, but Iris MacFarlane points out that “The Doctor Babu,…was trained in Bengali and didn’t speak any of the patients’ languages”. In 2008 SOMO reported that “medical care is not always adequate” although “Pesticides are often applied without proper protection,” and “Back pains, fractures from falling and respiratory illnesses are common.” War on Want echoed this in 2010. And Columbia Law School said in 2014 that “callous and inadequate medical care were cited by workers as the trigger for violent labor disputes on at least three plantations in recent years.”

So, what’s to be done…?

So what do these organisations recommend should be done about these deeply embedded problems? The plethora of suggestions boil down to a few simple recommendations for how consumers, retailers, buying companies, and plantation owners alike can take responsibility for the rights of those who make their industry possible.

- Pay more for tea – a price that enables workers to be paid sufficient to live a decent life.

- Obey the law – Whatever the failings of the Plantations Labour Act, it is the law and therefore should be obeyed. If prices are too low to enable this, see 1.

- Respect workers’ rights – as delineated in the Declaration of Human Rights and the International Labour Organisation Conventions. If prices are too low to enable this, see 1.

- Be transparent – On the back of the tea packet depicting the smiling lady merrily plucking tea in the gentle sunshine, say exactly where the tea was grown so that civil society can help ensure those smiles are real.

“Not another decade without justice…”

The New Year message of Nazdeek – the organisation which has done so much to empower tea workers to fight for their legal rights – makes the plea: “Not another decade without justice.” I second that plea with all my heart. Let us not tolerate another decade of poverty for tea workers. Another decade of malnutrition. Another decade of crumbling hovels. Another decade of cholera-infested water. Another decade of work that makes you sick but provides no cure. And certainly not another two centuries – without justice for tea workers.

Let’s look forward to a decade in which tea producers are paid enough for their tea to make it possible for their workers to claim their rights to decent pay, housing, healthcare and water.

You’ll join me in drinking a cup of kindness to that, won’t you?

Read the full literature review Human Rights in Assam Tea Estates – The Long View

[i] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-34513824

[ii] Cotton, Henry. Indian and Home Memories. Fisher Unwin. 1910

[iii] Because of the Plantations Labour Act, the conditions found at the Indian estate directly violate Indian law. Gita Bharali, ‘TheTea Crisis, Heath Insecurity and Plantation Labourers’ Unrest’, in Society, Social Change and Sustainable Development, North Bengal University, 2007

[iv] Letters from Alick & John Carnegie (British tea estate managers), quoted in Green Gold, Alan Iris MacFarlane, 1955. Ebury Press, (2004)

Happy Womens Day? Not just yet…

I’ve received lots of cheery “happy women’s day” messages today, replete with smiley emojis, pink bows and red roses, for which – of course – I’m grateful. I wouldn’t be so churlish as to remind my kind well-wishers that the first National Woman’s Day was actually designated by the Socialist Party of America in honour of the 1908 women garment workers’ strike in New York. But you don’t mind if I remind you, do you?

Women’s Day is now International and all the way across the globe from New York, on a green hilltop in South India, right at this moment a woman called Rajeshwari is settling down for the night on the floor of her three room house, her daughter by her side. Her husband and son are asleep on the bed beside her, and her mother-in-law in the next room.

Rajeshwari’s rest is well earned. When I met her a few weeks ago, she had just bathed after a long day plucking tea – as she does six days of every week. The more she plucks the more she earns to support her family – but then, of course, the more she has to carry up those steep High Range hills. I first heard of Rajeshwari in 2015 when she and three or four other women led an uprising of women tea workers demanding better pay and conditions – which I have written about before (ad nauseam?).

Witnessing that strike – against male management, politicians and even trade unions – made me determined to find a way to support these courageous women. After much soul-searching, blogging, tweeting, consulting with colleagues and friends in my network of human rights and labour rights experts, I decided to set up a new organisation called THIRST – The International Roundtable for Sustainable Tea.

My hope is that it will bring together the many other organisations, big and small, around the world, who have been working to improve conditions on tea plantations – where the vast majority of the workforce are women. The combined forces of trade unions, international NGOs, local campaigning organisations, academic institutions could be a powerful force for good. All the more powerful for acting in unity.

On top of her job as a tea plucker, Rajeshwari is also General Secretary of Pempila Orumai – the women’s trade union established as a result of the strike. It means Unity of Women. And to me that is what International Women’s Day is all about. Its about showing solidarity with women like Rajeshwari and her four thousand colleagues who had the courage to stand up for their rights. It’s about working in unity with them and for them.

So when every woman in the world is earning enough to live on – to actually live decently on, not just survive – without having to carry back-breaking loads, when every woman is sleeping on a bed (beside her partner if she has one) and is represented by as many women trade unionists and politicians as men, and when at least half the managers in every company women work for are women – then I will cheerfully join you in sending smiley-face emojis saying Happy Women’s Day.

Shackled by the tea supply chain….

Did you know that the name ‘Tesco’ is a combination of the names of Jack COhen, the supermarket’s founder, and T.E.Stockwell who supplied him with tea?

Did you know that the name ‘Tesco’ is a combination of the names of Jack COhen, the supermarket’s founder, and T.E.Stockwell who supplied him with tea?

Jack – aka “Slasher” Cohen – had an eye for an opportunity. At the end of the Great War he used his demob money from the Royal Flying Corp to buy army surplus food, and sold it to hungry, impoverished, war-weary Londoners on an East End market stall. He made a £1 profit on £4 of sales that day. This year, Tesco made £1,644 million profit on £51 billion of sales. Clever chap!

Tea, provided by Mr Stockewell, was Tesco’s first own-brand product, and recently – with discounters Aldi and Lidl snapping at its heels – it has come a full circle and started stocking Stockwell tea again.

And it’s marvellous value. Only 50p for a pack of 80 tea bags! How do they do it?!

No, seriously. How DO they manage to sell a product that’s plucked laboriously by hand, (on tea estates that have to house, feed, educate and provide healthcare for each worker’s entire family), that’s processed in vast factories, transported thousands of miles from India, Africa, Sri Lanka and other far flung countries (the pack doesn’t specify), packed in tea bags that are packed in boxes, that are transported to warehouses and thence to stores where people are paid to put them on shelves and sell them?

In May 2018 the average price of a kilo of tea from the Mombassa tea auction (one of the two main sources of the tea we drink – the other is the Kolkatta auction) was £1.82. So they paid about 36 pence for the 200g of tea that’s in the Stockwell box of 80 – leaving 14 pence for all the rest.

And to cover the profit margins of the tea producers, traders, transporters, packers, branders, advertisers, and retailers along the way.

And what about that 36 pence? Was that sufficient to adequately pay all those workers and look after their families? An endless stream of news articles, academic reports, trade union actions and NGO studies should tell you the answer to that. (It’s No, by the way).

In India, for example, workers are not even paid the national minimum wage. Their employers say they are hamstrung by the Plantation Labour Act regulations that compel them to support not just the workers, but also their families. This can mean that for a plantation with 1,000 workers, the tea company has to provide for, say, 6,000 people (counting children and elderly relatives). So they include these benefits in the wage calculation.

So maybe Tesco is taking the hit – sacrificing profit on a “loss-leader” to lure customers away from the siren call of the German discounters. But even if that’s the case, it leaves the entire supply chain impoverished. And with its new “strategic alliance” with French retail giant Carrefour, Tesco is promising even lower prices…

Can you blame them? Tesco topped Oxfam’s Supermarket Scorecard launched last month as part of its Behind the Barcodes campaign on public policies that protect workers’ and farmers’rights – but how long can it keep that up when it’s fighting pernicious price wars?

Sainsburys got into hot water last year for publicly moving from Fairtrade tea to its own “fairly traded” model (which campaigners criticised for disempowering growers) – but have you noticed that it’s much harder to find Fairtrade products in Tesco now too? At least its Stockwell tea is Rainforest Alliance certified…

It seems that the tea supply chain shackles and traps everyone in it in some way. From producers shackled by low prices and thousands of dependants, to retailers caught in a vicious, ‘race-to-the-bottom’ price war.

But someone, somewhere, must be making good money from the vast trade in the world’s second most popular drink after water.

And none are so shackled, so impoverished, so disempowered and so much in need of your support as the workers who picked the tea in your 0.006 pence tea bag.

What can you do? Well, for a start you can “use your consumer power” and contact your supermarket as Oxfam suggests. You can also do as Traidcraft suggests and ask the big British tea brands Who Picked My Tea?

Poverty, too, is a form of abuse…

On February 26th, while Oxfam and the wider aid sector slipped mercifully out of the headlines and knuckled down to the long haul of exorcising their demons and rebuilding the trust of their supporters, Fairtrade Fortnight began.

For those who have suffered at the hands of powerful men and have finally felt heard, and for all women, I hope this leads to redress and to greater safety and respect at work.

For those who believe everything they see in the media, it will be a break from the sense of shock and betrayal at the relentless onslaught of revelations of misconduct in a sector that exists to end suffering, not to create it.

And for those who know (most of) the complex, messy truth behind the media headlines, it will be a break from the sense of being under a sustained and deliberate attack (even if a small part of it may be justified).

So why should we care about Fairtrade Fortnight? Compared to these horribly serious issues, what’s so important about a cheery logo on a chocolate bar or a pack of teabags?

Because, my friends, it’s all about power.

Men who sexually harass or take advantage of women in any sector are abusing positions of power. And as affluent consumers we wield far more power than we perhaps realise. But we’re not affluent, I hear you cry. Yes we are – we may not be billionaires like those mentioned in Oxfam’s inequality report – but compared to the legions who produce our food, we really are.

And every time we go grocery shopping we have the power to make a choice. A choice that will directly impact on the women and men – and sometimes children – who produced the food we’re buying.

I don’t make this comparison lightly. Poverty, too, is a form of abuse.

Extreme poverty makes women and men vulnerable to harassment and humiliation every day of their lives, often with no escape and no hope of redress.

Poverty – and the powerlessness that goes with it – means having to work long, back-breaking hours, having to choose to send your child to work rather than school. It means not being able to afford treatment when you or your child is sick, or getting trapped into debt to pay for it.

It means being vulnerable to abuse – including sexual abuse – every day; abuse from those with the power to directly buy your products, to set the price for them, to give you work on their farms, and to supervise that work. And the power to lend you money when you or your child is sick.

And much of the food we buy is grown and processed by women and men in extreme poverty. Fairtrade certified food less so. It’s as simple as that.

The Fairtrade Foundation has put together a powerful short film challenging us to think how we would react if the inequality and exploitation in our food supply chains were up close and personal. It shows weary African children delivering food to nice, middle class homes. The homeowners are horrified and berate the children’s supervisor, who replies cheerily that “If you want low, low prices, this is part of the price”.

Think about it. When you can buy 45 teabags for 25 pence what impact do you think that has on the industry that produces the tea? Or the wages tea producers can afford to pay their workers, or their ability to provide decent housing, healthcare and sanitation?

Study after study has shown that Fairtrade certified farmers are usually better off, and have more say in what they earn and in how profits are spent. A study by the ODI, for example, claims “The evidence clearly indicates that certified producers have benefited from higher prices through Fairtrade certified sales, during periods of low conventional market prices.”

As Sandra Joseph, a banana farmer in the Winward Islands so powerfully put it, “Without the intervention of Fairtrade we would be fighting a losing battle. Fairtrade is our last best chance, our choice, our future… bananas are finished without Fairtrade.”

In the spirit of transparency, I must tell you that this is not the full picture. Fairtrade is not perfect. There are some circumstances, in the exponential complexity of this global trading system that we are all caught in, where Fairtrade has failed so far to lift the poorest out of poverty.

Nevertheless, I am a strong believer in the idea that offering farmers a stable price, access to markets, technical support and a premium to spend on the community has to be better on the whole than leaving them defenceless to the ferocity of global market forces.

And I do believe that Fairtrade can and has helped to even up the power imbalance a little (and sometimes a lot) so that thousands of women and men could escape extreme poverty and live more dignified, empowered lives. (Incidentally, Fairtrade was founded in 1992 by a group of organisations, including Oxfam.)

This year’s Fairtrade Fortnight message is “With Fairtrade we have the power to change the world every day”.

So please, let’s not abuse our power. Let’s use it for good.

The Oxfam I know… facts, rights and wrongs

Oxfam is under attack. Some would say rightly so. It allowed sexual predators to be employed – repeatedly – in situations in which women were vulnerable to their power and abuse. And that was absolutely wrong.

When that happened – seven years ago – it launched an investigation, got rid of the perpetrators, issued a press release, informed the Charity Commission and its donors, and then put in place stronger safeguarding measures and channels for people to be able to report abuses. And that was mostly right.

In the middle of managing that huge and complex natural disaster response it had to make some tough decisions – it didn’t report it to the local police, or go into the full details of the misconduct in its public reports – and I don’t know, maybe that was partly or wholly wrong.

The safeguarding system it put in place was starting to work – allowing more cases of abuse to emerge. The safeguarding team asked for more resources and, although not immediately, they were ultimately boosted – and that was a wrong that was at least partially put right.

In January, Oxfam launched a report called “Reward Work, Not Wealth: To end the inequality crisis, we must build an economy for ordinary working people, not the rich and powerful.” And that, in my view is right, but it attracted the ire of some of the rich and powerful.

On Friday Feb 9th (the day that Jacob Rees Mogg presented a Daily Express petition to Downing Street against foreign aid) The Times published the story of the sexual misconduct story from seven years earlier.

Oxfam has apologised repeatedly and sincerely for its mistakes. It has committed to putting in place even stronger safeguarding measures, being even more transparent, working with other aid agencies to make it even more difficult for sexual predators to move between agencies. And that is absolutely right.

But what is so heartbreaking is that the whole of this amazing organisation is being tarred with the same brush, a brush charged with half-truths and vested interests. My colleagues are being attacked and abused, accused of vanity, arrogance, greed, selfishness… and that is so, so wrong.

The Oxfam I know is an organisation that is deeply committed not just to ending the hunger and suffering of millions of people around the world, but finding out – through painstaking research – why they are hungry and suffering and doing something about that too.

The Oxfam I know is a collection of incredibly committed, unbelievably hardworking, thoughtful people who do not by any means see themselves as saints or put themselves on a pedestal above others, but who are simply responding to a strong sense of injustice in the world. As the Guardian journalist who visited Oxfam recently reported, they are heartbroken, angry, distraught – one colleague who has dedicated over 30 years of her life to the organisation described it feeling like “a bereavement.”

The Oxfam I know provided food and medical care to thousands of refugees from the newly formed Bangladesh through my grandparents’ Social Welfare Society in West Bengal.

The Oxfam I know brought doctors to a remote forest in central India to treat tribal people who had no access to medical care – including the man who told me his harrowing story of an infected leg that stopped him from being able to earn his living as a farmer, of going from hospital to hospital but being unable to pay for the treatment he needed, and of being ready to give up and die, before Oxfam provided the treatment he needed and literally saved his life.

The Oxfam I know responds immediately and pragmatically to disasters, like the 2004 Tsunami, when I helped in the communication hub and heard the reports coming in from all the affected countries about the food, housing, water, sanitation, clothing, medicines being rushed in.

The Oxfam I know enables incredible individuals – Indian, South African, Malawian, Bosnian, Zimbabwean, Zambian, Filipino, Haitian etc colleagues – to dedicate their lives to helping the people of their own countries.

The Oxfam I know consists of women and men who repeatedly fly into the most dangerous situations in the world, leaving behind the comfort and safety of their homes and their families to work day and night to help fellow human beings survive wars, earthquakes, volcanoes, epidemics… without abusing sex workers.

And all that is so, so right.

If you – like me – still believe in Oxfam and its work, please send a much needed message of support. And go into an Oxfam shop to hug a volunteer. (It’s ok – there are strong safeguarding measures in place there too.)

Tea workers deserve rights – not charity

This morning I posted this on Facebook:

“On this 70th International Human Rights day, I am sitting with a nice, hot cup of tea, looking out at the snow falling, as if on cue, just in time for me and my daughter (who gave me the flattering mug!) to get in the Christmas mood and start putting up the decorations.

Thousands of miles away, by contrast, the people who grew the tea I’m drinking face blistering hot sun, carrying back-breaking loads of tea (they’re paid by weight), and the danger of meeting wild elephants on the way back to their two-room huts… That’s why a group in Assam is calling on us to observe Human Rights Day as *Tea Workers Rights Day*.

So please join me, if you will, as I raise my cup of Munnar tea, raise your Tetleys, your PG tips, your lapsang suchongs, your Earl Greys, your Lady Greys and your decaff Tesco own brand… and make a toast “To tea workers’ human rights!”

And then maybe go and make some toast to go with your tea.”

Moments later, Facebook, doubtless having detected a whiff of altruism in my post, suggested that I might like to add a ‘donate’ button to my post to raise money for my “charity”.

But that’s the awful irony – why should workers in a multi-million pound global industry, producing the second most popular drink in the world after water, including brands that are named and prized for their distinctive quality – Assam, Darjeeling, Ceylon – be in need of charity? Or, indeed, in need of food rations from their employers?

This industry, which is predicated on cheap and plentiful manual labour, and on low, low prices – restricting the ability of those employers to pay decent wages – needs a jolly good shake up.

And it starts with you making that toast.

I mean the toast to tea workers rights, not the toast you made to go with the tea.

If but for a single instant you could see this world the way it really is…

“By introducing properly prepared mascons to the brain, one can mask any object in the outside world behind a fictitious image—superimposed—and with such dexterity, that the psychemasconated subject cannot tell which of his perceptions have been altered, and which have not. If but for a single instant you could see this world of ours the way it really is—undoctored, unadulterated, uncensored—you would drop in your tracks!”

This is a passage from an extraordinary book I read as a teenager called The Futurological Congress. I have since been haunted by the image it portrays of a world in which people have the impression that they are blissfully happy and have all the comforts of life, delicious food, comfortable homes, beautiful clothes. But the reality – which the hero is able to see after taking a dose of up’n’at’m, the antidote to mascon – is that they are dressed in rags, eating gruel from troughs and clambering up empty lift shafts (the hero always wondered why people were so out of breath when they came out of the lift…).

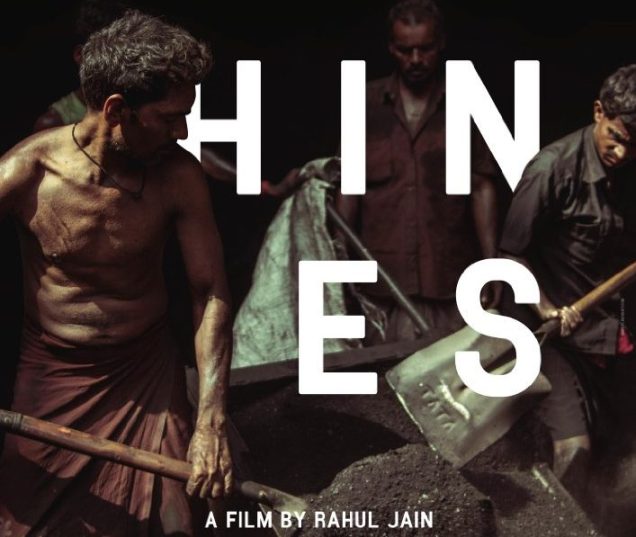

Tonight I saw a film called ‘Machines’ by Rahul Jain. It is the cinematic equivalent of up’n’at’m. It is not the first film to strip away the illusion of the seductive images of life that advertising constantly sleets into our consciousness, to reveal the mind-numbing drudgery, brutality and ugliness of cheap labour production. But it is one of the most powerful I have seen.

It absolutely made me drop in my tracks.

The only music is the ceaseless thrumming of the machines (the mechanical ones). Human “machines” silently tend the mechanical ones – stoking their fiery throats, oiling their antediluvian limbs, feeding endless rivers of pure white or brightly coloured fabric through their roaring rollers, heaving vats of the dark and poisonous dye or the giant bales of intricately patterned voille that it miraculously transforms into. (One of the most striking things about Jain’s film is how beautiful he makes the ugliness of industrial dirt and poverty.)

The only voice is when – very occasionally – the workers speak. Several – with quiet resignation – speak of their 12 hour shifts and their inability to educate their children on their pitiful pay. One (literally looking over his shoulder) about the fear of unionising, another of the futility of attempting to do so.

A young boy – of roughly GCSE age – describes how every day when he arrives at the factory gates his gut tells him to turn round and run away… but he has no choice but to go in to start his 12 hour shift. (Later, we see another boy his age repeatedly nodding off and almost toppling into the machine he is monotonously tending.) He has swallowed the line he’s been fed that by starting young he’ll learn valuable skills. But the adults reveal that this is no life to aspire to. It is a life that they have no choice but to accept due to their poverty.

Another worker says that all he knows is his room and the area of the factory where he works solidly from the time he wakes to the time he sleeps – he has never set eyes on the factory owner, has no idea who he is or what he looks like.

The next image is of said factory owner, predictably plump and well-to-do, who seems to know the workers a lot better than they know him. He explains the importance of keeping the workers a little hungry because if they get too comfortable they will tell the company to “fuck off”. He also explains that 50% of the workers do not care about their families and if he paid them more they would just spend it on alcohol and tobacco.

One man denies that this is exploitation, because he has chosen – even got into debt – to come from hundreds of miles away to work here. And is grateful for it. “Poverty is harassment.” he explains. And adds, with the universal fatalism of the poor the world over, “There is no cure.”

But he is wrong. There is a cure.

The cure is workers uniting and demanding their internationally agreed rights (even the suitably villainous looking contractor knows that it is the disunity of the workers – migrants from other impoverished parts of India – that makes them vulnerable).

The cure is the government enforcing its laws on child labour, health and safety, working hours and minimum pay.

The cure is us – you – the consumer making it known loud and clear that yes we are always happy to find a bargain, but not at the cost of turning men into machines.

Jain (unseen and unheard by us) is confronted by the workers at one point. Because we dont see him, they are, in effect, confronting us. They accuse him (us) of being just like all the others – like the politicians coming and hearing their tragic story and then going away and doing nothing about it. “Help us get 8 hour shifts instead of 12,” he says. “Tell us what to do and we’ll do it – won’t we, brothers?” His co-workers punch the air and shout their assent.

They are the cure.

Assuming they are not sacked for unionising (there are plenty more poor to take their place), and their fledgling leader doesn’t mysteriously disappear…

Jain does his bit to support them by showing us his film. Now what can we do to support them?

Image: Wallpaperflare.com

Image: Wallpaperflare.com