Exactly half way through this last decade, the women tea workers of Munnar in South India rose up and said ‘Enough’. They demonstrated against the tea company for keeping them in poverty, against the trade unions for not representing them fairly, and against the politicians not doing anything to protect them. Many tea-pun headlines later, the world’s media concluded that this plucky group of women had “won”[i] (their 20% bonus) and moved on to fresher stories.

Exactly half way through this last decade, the women tea workers of Munnar in South India rose up and said ‘Enough’. They demonstrated against the tea company for keeping them in poverty, against the trade unions for not representing them fairly, and against the politicians not doing anything to protect them. Many tea-pun headlines later, the world’s media concluded that this plucky group of women had “won”[i] (their 20% bonus) and moved on to fresher stories.

Meanwhile the women remain in their tiny dilapidated houses, the bonus that they fought for reverted to the earlier lower rate, their daily wage rate increased slightly but only on condition that they plucked yet more tea.

As the new decade begins, the age old problems persist. But I strongly believe that the tea industry has the power to change. The catalogue of problems that follows does not have to reflect the decade to come. But it can inform a determination to turn the industry around and adopt pricing and labour practices that invite admiration rather than criticism.

“The more things change…”

And a lot has changed in India in the 200 years since tea was first planted there. Independence. Land redistribution by the Communist governments of tea-growing states, Kerala and West Bengal. A burgeoning middle class. Soaring GDP. Yet somehow tea estate workers remain exempt from progress – kept frozen in 19th century feudalism and penury.

The pitifully low wages paid to them, the shoddiness of their housing, their lack of access to clean water and to decent healthcare has come up before.

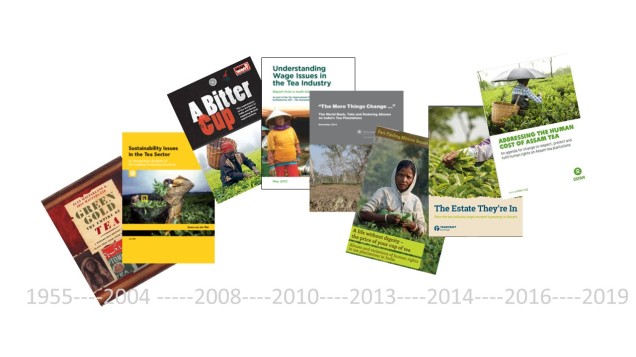

In 1866, 1900, 1955, 2004, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2019 to be precise. There are many, many other instances of these issues being raised, but these are the dates of the reports by NGOs, trade unions, the media and academic institutions that I reviewed last year for THIRST – The International Roundtable for Sustainable Tea – to trace just how long the problems have persisted, with a focus on Assam.

The answer seems to be… from the very beginning.

That’s why Columbia Law School entitled their 2014 report, “The More Things Change…” referencing the epigram “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” or “the more things change, the more they are the same.”

“below the poverty line” & “life-threatening malnutrition…”

Low wages reported in 1900, 2008, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2019

In 1900, the Chief Commissioner of Assam, Henry Cotton, wrote of tea workers there: “Not only were their lives worse than that of American Slaves but their living and working conditions were also deplorable… Their wages remained frozen at the rate of Rs 5 per month for men and Rs 4 for women established by a statute in 1865.[ii]”

One hundred and eight years later SOMO said; “… malnutrition on tea estates is still a big problem which leads to all kinds of medical problems including in some cases infant death and starvation.” Two years after that, War on Want reported “The children of tea workers in Assam suffer due to their parents’ low wages and miserable living conditions, as evidenced by the high prevalence of malnutrition.” And in 2016 The Global Network on the Right To Food and Nutrition (GNRTFN) found evidence of “several malnutrition-related deaths” due to management failing to provide mandatory food rations (which are considered part of the pay package).

Columbia Law School, in 2014, raises the issue of deductions from these low wages – an issue raised by Cotton one hundred and thirteen years earlier; “In some instances only a few annas (or pence) found their way into the hands of a coolie as wages in the course of a whole year, the managers having deemed that they were justified in making deductions right and left so long as they kept their labourers in good condition like their horses and their cattle.”

Traidcraft reminds us in 2019 that; “women working on tea estates are paid significantly less than those working in other areas of agriculture, for what is difficult and skilled work.” And Oxfam reports that official recognition of tea workers’ poverty is evidenced by the fact that, shockingly, “half of households interviewed receive government ‘Below Poverty Line’ ration cards.”

“cramped quarters with cracked walls and broken roofs…”

Inadequate housing reported in 1955, 2010, 2014, 2016 and 2019

Iris MacFarlane – the wife of a tea plantation manager in the 1950’s – described workers’ accommodation as “…rows of thatched hovels sharing a communal tap.” By the time War on Want reports in 2010, the situation is not much better; “Whilst housing is provided, it is of poor quality and in need of maintenance.” The theme echoes again and again through the decades; Columbia Law School in 2014; workers “live crowded together in cramped quarters with cracked walls and broken roofs.” Traidcraft and Oxfam in 2019; “Houses are often extremely old and leaky and the management appears unwilling or unable to make the necessary repairs,” and “workers reported that leaking roofs have meant their families had to use umbrellas inside the house during the rainy season.”

“a network of cesspools…”

Lack of access to clean water and sanitation reported in 1955, 2010, 2014, 2016 and 2019

War on Want reported in 2010 that on Indian tea estates “access to safe drinking water is an acute problem,” citing a study[iii] that found “the same regrettable conditions were the norm rather than the exception.” Again, not much had changed since Iris MacFarlane saw several households sharing a single tap, and thought “No wonder the servants suffered from boils and colds.”

Further reports drip persistently through the ages: Traidcraft in 2019; “The lack of proper toilets throughout estates is a major threat to good hygiene standards”. Columbia Law School in 2014; “The failure to maintain latrines has turned some living areas into a network of cesspools…” Oxfam in 2019; “despite doctors’ warnings they have no choice but to drink the contaminated water, so diseases such as jaundice, cholera and typhoid are common.”

“they die here very easily…”

Poor healthcare reported in 1866, 1955, 2008, 2010, 2014 and 2019

A 1866 letter from an Assam tea plantation manager with no medical training describes his approach to medical care for 450 people; “ Every morning I have to administer oil of caster to a lot of them. I have splendid receipt for spleen and have cured a lot of chaps, and dysentery too, two of them are dead but they die here very easily so they don’t think much of that.”[iv]

By 1955 there were hospitals and doctors, but Iris MacFarlane points out that “The Doctor Babu,…was trained in Bengali and didn’t speak any of the patients’ languages”. In 2008 SOMO reported that “medical care is not always adequate” although “Pesticides are often applied without proper protection,” and “Back pains, fractures from falling and respiratory illnesses are common.” War on Want echoed this in 2010. And Columbia Law School said in 2014 that “callous and inadequate medical care were cited by workers as the trigger for violent labor disputes on at least three plantations in recent years.”

So, what’s to be done…?

So what do these organisations recommend should be done about these deeply embedded problems? The plethora of suggestions boil down to a few simple recommendations for how consumers, retailers, buying companies, and plantation owners alike can take responsibility for the rights of those who make their industry possible.

- Pay more for tea – a price that enables workers to be paid sufficient to live a decent life.

- Obey the law – Whatever the failings of the Plantations Labour Act, it is the law and therefore should be obeyed. If prices are too low to enable this, see 1.

- Respect workers’ rights – as delineated in the Declaration of Human Rights and the International Labour Organisation Conventions. If prices are too low to enable this, see 1.

- Be transparent – On the back of the tea packet depicting the smiling lady merrily plucking tea in the gentle sunshine, say exactly where the tea was grown so that civil society can help ensure those smiles are real.

“Not another decade without justice…”

The New Year message of Nazdeek – the organisation which has done so much to empower tea workers to fight for their legal rights – makes the plea: “Not another decade without justice.” I second that plea with all my heart. Let us not tolerate another decade of poverty for tea workers. Another decade of malnutrition. Another decade of crumbling hovels. Another decade of cholera-infested water. Another decade of work that makes you sick but provides no cure. And certainly not another two centuries – without justice for tea workers.

Let’s look forward to a decade in which tea producers are paid enough for their tea to make it possible for their workers to claim their rights to decent pay, housing, healthcare and water.

You’ll join me in drinking a cup of kindness to that, won’t you?

Read the full literature review Human Rights in Assam Tea Estates – The Long View

[i] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-34513824

[ii] Cotton, Henry. Indian and Home Memories. Fisher Unwin. 1910

[iii] Because of the Plantations Labour Act, the conditions found at the Indian estate directly violate Indian law. Gita Bharali, ‘TheTea Crisis, Heath Insecurity and Plantation Labourers’ Unrest’, in Society, Social Change and Sustainable Development, North Bengal University, 2007

[iv] Letters from Alick & John Carnegie (British tea estate managers), quoted in Green Gold, Alan Iris MacFarlane, 1955. Ebury Press, (2004)

On a chair opposite the Japanese Embassy in Seol, South Korea sits a statue. A life-sized figure of a young woman symbolizing the innocence that was violated by Japan when it forced 200,000 women from Korea and beyond to become sex slaves for their soldiers during WWII.

On a chair opposite the Japanese Embassy in Seol, South Korea sits a statue. A life-sized figure of a young woman symbolizing the innocence that was violated by Japan when it forced 200,000 women from Korea and beyond to become sex slaves for their soldiers during WWII.